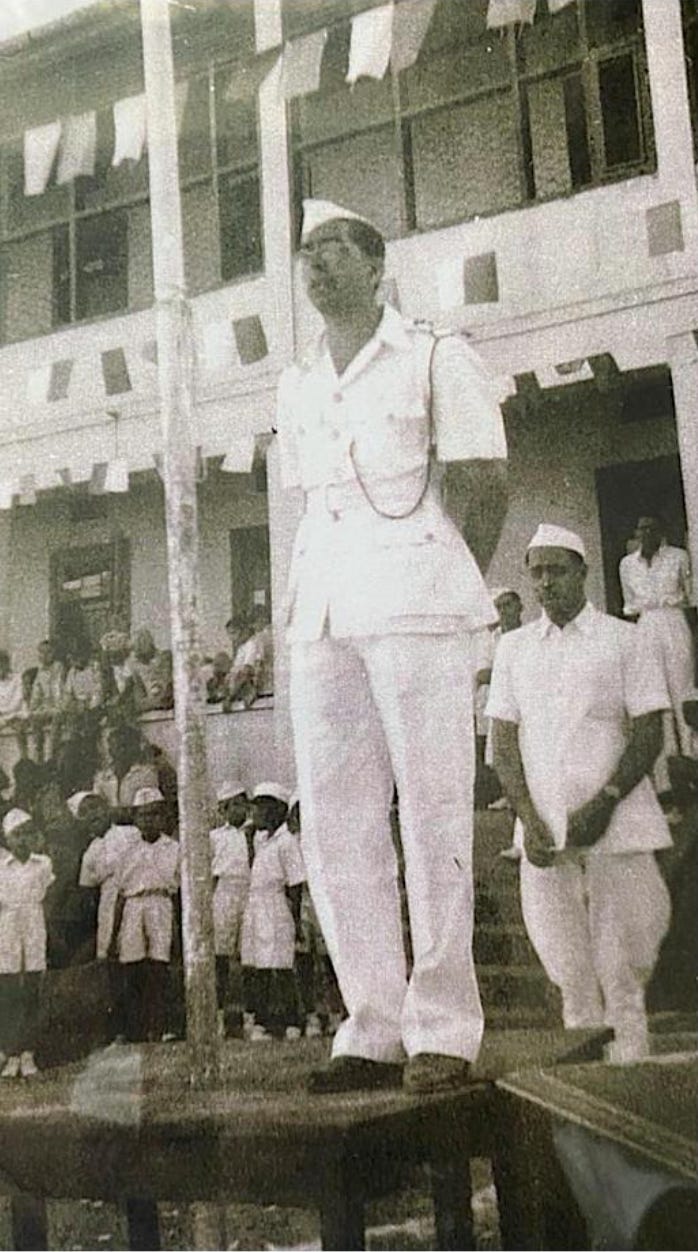

Bapuji was a man of motion. In the glory of his youth, he set sail for India to join the Independence Movement. He trained as a social worker at Gandhiji’s ashram on the Sabermati, devoting the rest of his life to community - founding schools, fundraising for temples and organising festivals. Ba rushed behind him, steadying the sails of his ambition with meeting minutes kept in careful hand and endless pours of chai. When his body began to fail, first his ears, then his eyes, his appetite and his strength, she was there reading to him, feeding him, bathing him. The captain of a sinking ship, she never left his side.

The mourning was intimate and traditional with Bapuji’s body kept at home overnight while his younger brother and only surviving sibling, Nana, flew in from Kisumu. They were the closest of confidants with the same smiling eyes and long-lobed ears. Nana’s presence and faith brought us all great comfort. For thirteen nights we gathered to pray in the small flat in suburban London, the script of ritual carrying our grief forward each day, and then when it was over, Nana flew home and our lives resumed. It was only Ba who was left unmoored, drifting through the hollowed apartment without urgency, writing notes instead of speaking. When I called to ask what vegetables she wanted from the shops, she could only name Bapuji’s favourites. She did not know what she liked to eat - no one had ever asked and she had not thought to ask herself. So she ate little, shrinking into the stillness he had left behind.

A few months after she was widowed, I asked Ba if she wanted to come with me to Kenya, the country where she and Bapuji were born and had lived for many years before moving to the UK in the seventies. She had not left the country in a decade. She scrawled out yeses and nos on dozens of paper scraps and scrunched them into balls. We both picked out yeses.

We broke up the journey with a night at my uncle’s place in Nairobi. He sent a driver, Fred, to pick us up from the airport. ‘What kind of name is Bread?’ Ba whispered to me. I couldn’t bear to correct her and so she giggled all the way to the house.

The night was heavy, and the fan wheezed as it cut through the humidity. Neither of us slept. Ba rose when dawn flooded through the windows. She cried a little. It was a Sunday and Bapuji had died on a Sunday. After a long shower, she pottered around the room, oiling her hair and applying red tilak to her forehead. She took a square of pink saree out of her suitcase and allowed it to unravel onto the floor before winding it slowly around her waist, carefully folding each pleat. Her face strained as she pinned the loose fabric onto her shoulder. She never wore sarees anymore, the blouses felt too tight and the pleats too heavy, but for Kisumu she would make an exception.

When we arrived, Nana was standing alone at Arrivals to greet us. He stood straight, bearing no weight on the walking stick in his hand. He too had dressed up, cleanly shaven in a cotton safari suit. He shuffled slowly towards us, thick lenses magnifying his watery eyes.

‘Jai Siya Ram bhabi,’ he bowed his head. ‘It’s good that you have come.’

‘Who would have thought we would be here alone,’ Ba replied as her tears fell.

Kisumu embraced us with its thick heat as he led us, very slowly, to the car.

The ride was mostly silent, an uneasy mix of awkwardness and exhaustion and the cloying nausea of warm upholstery. For many years, Ba and Bapuji and Nana and his wife, had travelled together, visiting pilgrimage sites, conducting charity work and attending family weddings. But despite this there was an air of formality between them, a deep respect.

Outside, the city dozed through the afternoon, its shops shuttered for lunch. Time inched forward. Ba had been a child when she moved here from Kakamega to marry Bapuji, ten years her senior. She watched the familiar streets roll passed, grown up and tarmacked, recognising pink facades and industrial signs, old landmarks that now felt flimsy and irrelevant. The cellophane on the car windows had bubbled in the heat, warping the world beyond it.

A truck of sugarcane rumbled passed, piled high. ‘Is the sugar factory still running?’ Ba asked cautiously.

‘It’s running,’ Nana smiled.

‘The printing press?’ she pressed further, her voice steadying. He nodded. ‘The mandir?’

‘Come, I’ll show you.’

**

Nana’s house was dark and cool and the tiled floor was a welcome relief for my bare feet.

‘First let me see her room,’ Ba said.

Nani’s room was exactly as it had been, besides from a large framed portrait of her which now watched over it. Ba walked over to the portrait and looked into Nani’s eyes.

‘Bhabi come, take lunch,’ Nana called.

The tears came as we sat down to eat.

‘It’s just that, this is exactly how she used to lay the table,’ Ba sobbed.

After lunch, Nana retired for his afternoon nap and Ba and I took a walk around the garden.

Kusuku, Nani’s large grey parrot perched on a wooden bar in a cage on the patio.

‘Kusuku,’ Ba cried. The bird peered at us, cocking her head from side to side. Ba tried again.

‘Tchk tchk tchk… Kusukuuuuu?’ she coaxed sweetly. The parrot only blinked. Ba reached through the bars, running a gentle finger along her feathers. Nani’s bird had lost her voice.

I took Ba’s hand and led her through the garden. The humid climate and fertile earth had conjured a jungle of riches.

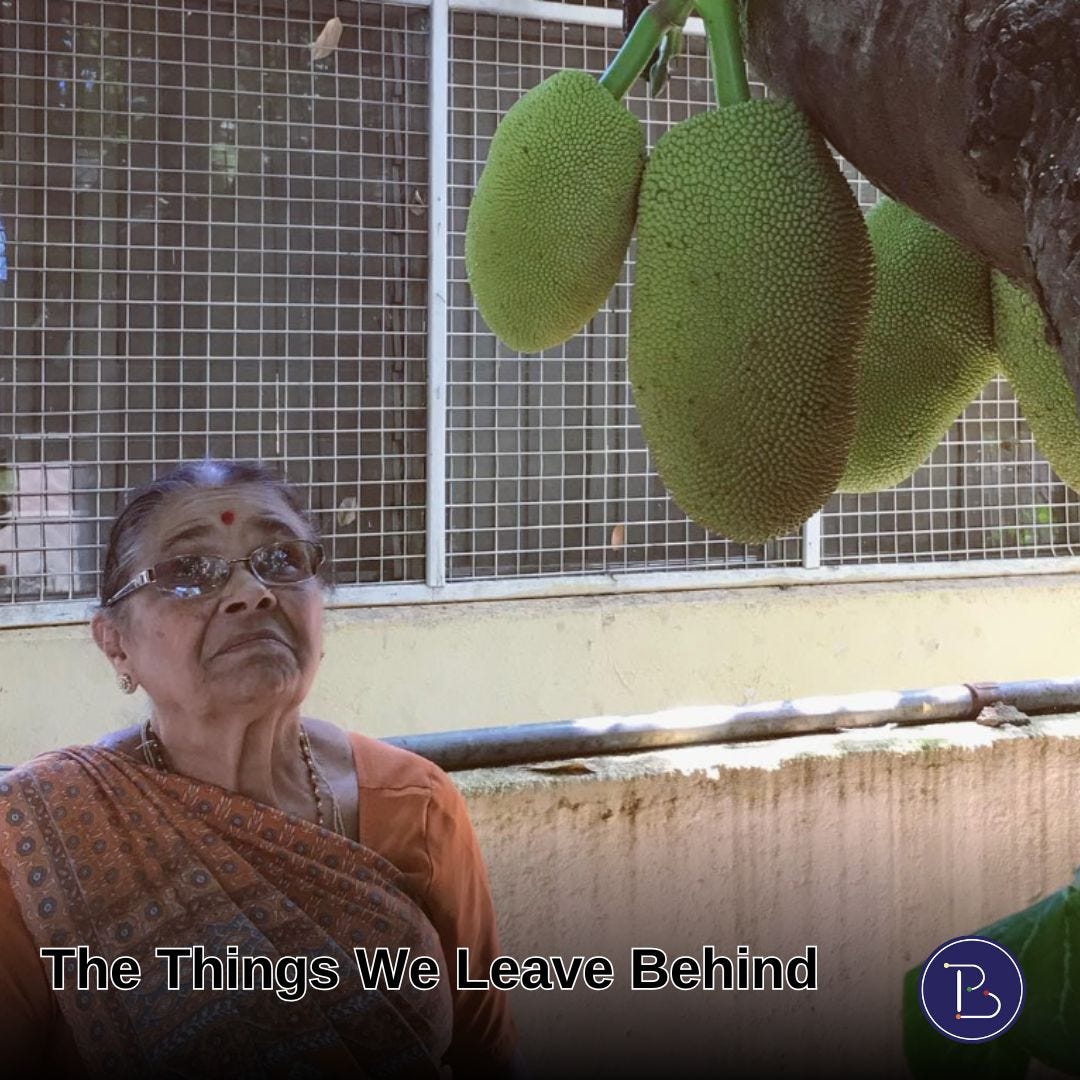

‘There was big limbdo tree here,’ Ba pointed. ‘And look at this jackfruit… and ambla, see small green fruits… in season they will be all over…’

Her hands traced the lush canopy.

‘In Kakamega I would climb with my friends to pick the ambla, but after marriage it was not allowed… everyday I would work in the kitchen and look at this tree, thinking how I would climb it… but I never got the chance… now I’m too old’ she chuckled.

When Nana awoke, we moved into the living room. There was a hinchko at the end of the large room. Nana swung gently. We sat on low armchairs that lined the walls. Time passed. For a moment, he looked like a king surveying his subjects. I imagined him on afternoons without us, a boy on a swing.

Ba wept again at dinner, affronted by an innocent bowl of rasgulla.

‘These were his favourite,’ she cried.

Bapuji had given up sugar in protest during the Quit India Movement and the novelty of eating sweet things again after Independence had never quite worn off.

‘And you gave him plenty. What is there to cry about? They can’t eat them anymore, bhabi. It is only us now… us and the rasgulla.’

She refused.

Nana insisted.

‘Let me show you,’ he said. He scooped a white ball out with a spoon and grabbed it in his fingers. ‘You have to squeeze it.’

Even in Nana’s weak grip the syrup pooled onto his plate.

‘Take one.’ He spooned out another ball and offered it to Ba. She followed his lead and squeezed out the syrup. For a brief moment their eyes met, inviting the uncharted friendship that lay before them. They looked away hastily and shovelled the white sponge into their mouths. Ba’s face scrunched with delight.

The next day, Nana took us to visit the school that he and Bapuji had founded in a nearby village. To celebrate Bapuji’s life Nana had prepared bags of gifts for the children; pink wafer biscuits, colouring pencils and juice boxes. Though the school was near, the roads were trying and Ba inhaled sharply each time the car jolted. The sun streamed through tinted windows, illuminating pillows of dust that rose to meet us. When the car could go no further, Nana ushered us out and guided us down the final stretch of track. We advanced slowly under the relentless sun, silent besides the dull thuds of two walking sticks hitting earth.

The headmaster welcomed us with bottles of water at the gate, and led us to some chairs beneath the shade of an old and weathered tree.

‘Your Bapuji planted this tree,’ Nana said. Ba brushed its bark, then rested her cheek against its study trunk. I asked for a picture of the two of them, and they straightened their backs, smiling, a careful metre apart.

‘Come,’ the headmaster said. ‘The children are waiting.’

The children had amassed in the field out back, and as we approached they began to sing, a joyous chorus ringing bright and sharp through the hot afternoon.

Ba’s gaze moved over their faces as if searching for someone. Towards the back, there were girls in green uniforms. They were fourteen or fifteen. The same age she had been when she had come to this town.

She watched them swaying as they sang, their voices lifting into the wet Kisumu air.

‘They are in secondary school?’ she asked softly.

‘Yes,’ the headmaster said proudly. ‘And some of them will go to college.’

The children finished their song and the headmaster called for applause. Ba clapped, but her gaze stayed fixed on the older girls.

‘Girls did not go for secondary in my time,’ she murmured. ‘Your Bapuji promised to change that.’

Nana addressed the crowd in Swahili and they listened intently before applauding. Ba remained silent, her hands pressed together in her lap. When it was time to distribute the sweets and pencils, she hesitated. The children lined up single file.

‘Go on,’ I urged, pressing a paper bag into her hands.

She moved carefully to the front of the line. The first child, a young girl, beamed as Ba handed her a bag. Ba’s eyes softened and she bent slightly to ask the girl a question, moving easily in her light cotton sari. Her voice slipped fluidly into Swahili, a language I’d never heard her speak. The words rose, effortless and whole, like a buried anchor resurfacing. The girl responded eagerly, and Ba nodded, asking something more. The line of children shuffled slowly forward, and Ba took her time with each one, listening and laughing, fluent once again in her childhood tongue.

When it was time to leave, we found that the driver had brought our car right up to the gate. With Ba and Nana buckled in, I took a last lingering look at the school: bright eyed young girls, pink wafers sticky in their hands, clambering up the branches of Bapuji’s tree.

Rhiya Pau is a British-born poet, performer and educator based in San Francisco. Her debut collection, Routes (Arachne Press, 2022) received an Eric Gregory Award from the Society of Authors. Commemorating fifty years since her family arrived in the UK, Routes chronicles the migratory history of Pau’s ancestors and navigates the conflicts of identity that arise within the East African-Indian diaspora. Rhiya won the Creative Future Writers’ Award (2021) and has been highly commended in the Forward Prize (2023) and the After The End Poetry Competition (2024). Her poems appear in Wasafiri, The Liminal Transit Review, Token Magazine, Off The Chest, and Third Space anthologies, among other places. You can follow her work on IG @rhi.write

The archive is still being written. The bridge is still being built. Got an idea, a story, or something we missed? Let’s collaborate—hit us up at BlindianProject2020@gmail.com.

This isn’t just a newsletter—it’s a conversation, a community, a blueprint. History is stitched together one thread at a time.